Recently, I undertook a certificate in sports data analytics through the Irish university ATU. The certificate involved two modules – one focused on the use of statistics in an academic context and the other on machine learning models and AI. Both modules were, in different ways, equally challenging and interesting.

I made a real effort to apply some of the ideas behind Relative Runs to our assignments, most notably in the course on machine learning models. I’ve had an interest in how things like regression models can be applied to cricket since seeing them mentioned in a couple of great books (Cricket 2.0 and Hitting Against the Spin, to my recollection). When we got onto how to build and analyse machine learning models, I couldn’t wait to play with them using Relative Runs.

I focused mostly on what are called logistic regression models, which, perhaps counterintuitively, are not a type of regression model, but rather a kind of classification model. What that means is that these models work by using input data to predict a binary output, rather than a continuous numerical output (which is broadly what regression models do). In short, these models are using input data to predict one of two classes, hence the name ‘classification model’. These two classes can be any variety of binary feature, from wins and losses to an injury occurrence or non-occurrence.

In the case of my model, I wanted to look at how Relative Runs could be used to predict overall performance success. What I had was my analysis of the 2025 IPL season, including Relative Runs scores for all the top batsmen across that season. What I wanted to pair that with was some kind of binary output feature that I could double as an indicator of overall tournament success. This is tricky conceptually because we are starting with a player metric, and we want to know whether this input feature bears some relationship with an output team metric.

At first, I was not optimistic that this route would be anything other than an interesting academic exercise. It proved more than that, however!

I chose as my output variable the binary feature of whether a player’s team made the playoffs or not. That is, whether or not that player’s team finished in the top 4 or bottom 6 at the end of the regular season. In essence, the idea here was to say, rather than splitting the table in half, let’s split it into post-season entry or not. Most IPL franchises would deem making the playoffs as a key indicator of success, and in many ways, that is what they are buying when they build teams – they are paying to make the playoffs (and then hopefully win it all). If there is some underlying relationship between a stat like Relative Runs and team performance, making the playoffs is a good metric to start with in terms of testing that relationship out.

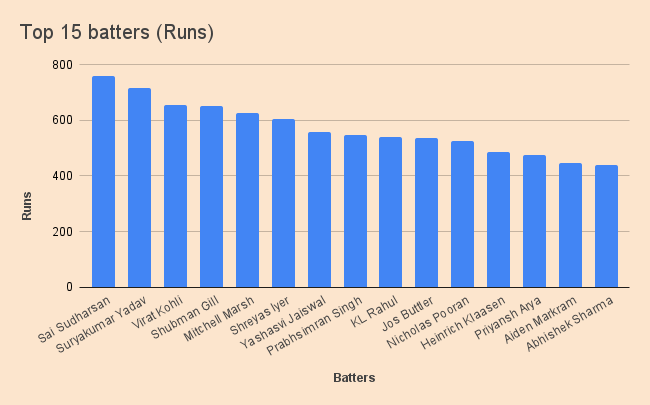

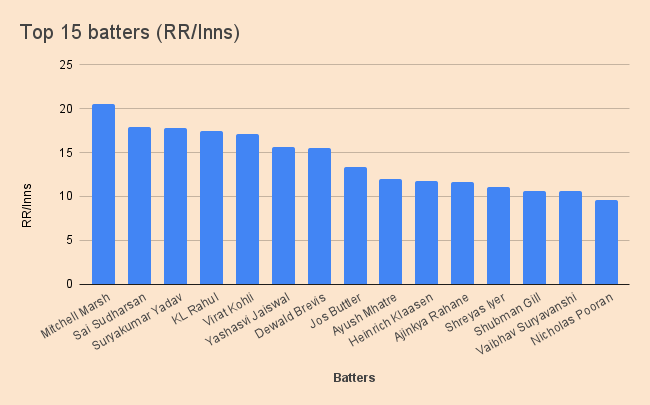

So I had my output variable: making the playoffs or not. What I wanted to know next was whether there is a meaningful predictive relationship between certain input player metrics and that output variable. As input variables, I chose to focus on runs, strike rate, and Relative Runs per Innings. I ran logistic regression models to ascertain which of those inputs generated the best models in terms of predicting teams’ success, as measured by making the playoffs. And what’s more, I also tested combinations of those input variables with the same output target. The results were more interesting than I expected!

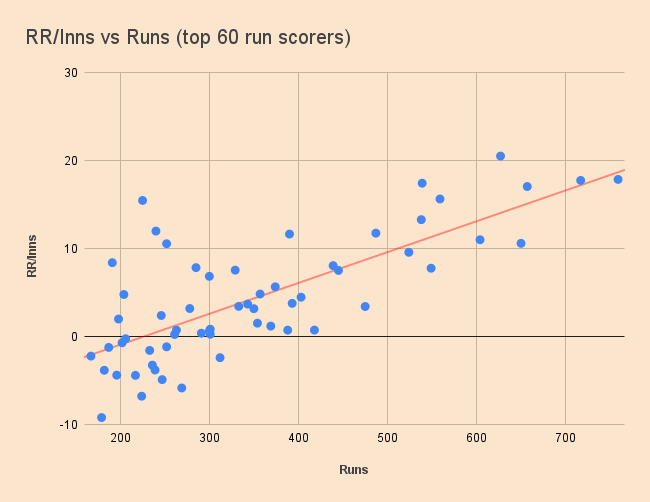

First, regarding the tests with one player metric as input, the model with runs as the only input variable performed worst in terms of predictive accuracy, followed by strike rate, then by Relative Runs per innings. What this means, in short, is that according to the dataset used (which, granted, was only using the top 50 batters in the 2025 IPL), Relative Runs per Innings was the best predictor of team success of those three individual metrics, when using logistic regression. The model accuracy was only 0.67, and the precision was 0.5, which isn’t great, but it was the best of the three, which pleasantly surprised me.

Combining the input variables was even more fascinating. You’d think more input variables mean more accuracy in the models, and that’s broadly what I found to be true.

I ran models that used Relative Runs per Innings + strike rate, Relative Runs per Innings + runs, and lastly, all three together. The worst of those was Relative Runs per Innings + strike rate, while the other two generated the same key evaluation scores, so I put them both through what’s called a ‘k-fold cross validation’, which runs the model ‘k times’ using different slices of data. That extra step showed that the model using runs and Relative Runs per Innings was more accurate than the model which used all three input variables, curiously. This could be proof that the strike rate actually created noise in the model, as including it hindered accuracy.

The mean accuracy of the best model was 0.7. What does this mean? In short, it means that the model, which used Relative Runs per Innings and runs as inputs, correctly predicted the output of making the playoffs or not 70% of the time. That’s not an astronomical result, but what is really encouraging from these models is that it gives proof that Relative Runs improved the accuracy of the models in terms of predictive success, and actually bore a stronger relationship with team success than both players’ runs and strike rate did on their own.

Of course, it should be remembered that this is all based on one rather small dataset, but still, that is a fascinating result and a good indication of how Relative Runs could be used going forward. If the stat bears a strong relationship with team success, it could be a very useful tool for talent identification. Going big picture, we often scan the run charts and strike rates of batsmen in tournaments to find ‘the best’ players… But perhaps Relative Runs is a better starting point for these conversations than either of those traditional stats. Bigger datasets and more nuanced models will add depth to that conversation.

I also dipped into regression models using the same three inputs, but with the output variable of the teams’ final rankings in the season, from 1 to 10. These regressions were interesting, but pretty much every combination of inputs resulted in fairly inaccurate models. That was probably down to the fact that using rank as a target output was not a great choice, and I’d try the whole process again with a finer-grained metric, such as win percentage. That is, I’d like to discover whether there is a good model to be made out of the relationship between Relative Runs and runs as inputs, and players’ win percentages as outputs.

Broadly speaking, the logistic regression analyses worked a lot better, but there’s room to do a lot more regression analyses. Indeed, there’s room to do a lot more research with both types of models using much larger datasets, and utilising more varieties of the Relative Runs universe: that is, Relative Strike Rate, Relative Economy.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into my machine learning model analyses using Relative Runs, here is a pdf copy of my submitted report.

Another cool component of the certificate I completed was learning how to use Power BI to create reports and dashboards. If you have a Power BI account, you can take a look via this link at a report I built to display the batting stats of the top 49 batters from the 2025 IPL season, including Relative Runs and Relative Runs per Innings.