The 2025 Champions Trophy (CT) in Pakistan/UAE has come and gone, so let’s take a look at the best batters and bowlers from the tournament using Relative Runs (RR) and the associated stat of Relative Economy (REc).

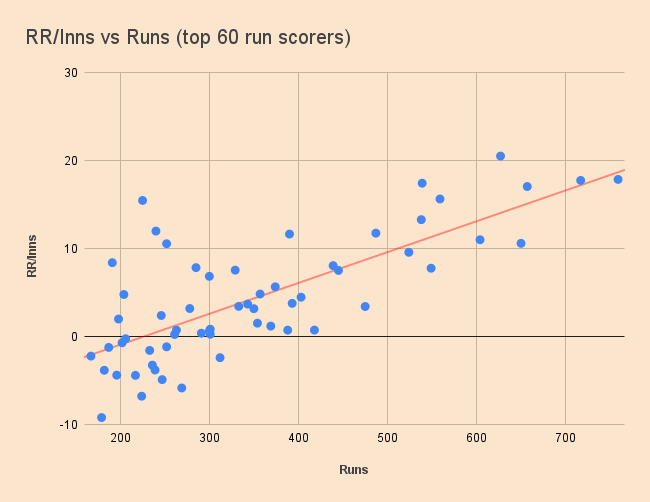

A few things jump out about the CT just glancing at the tournament. In Lahore and Karachi, a par score was around 320, while over in Dubai, where India played all their matches, 260 was enough to win all but one match. Just those facts alone play into the hands of Relative Runs as a tool.

Obviously, the value of runs is different at each of those venues, not to mention Rawalpindi. Trivially, scoring 50 means more in a total of 250 than in a total of 350. Equally, a bowler going at 6 runs an over in an innings over 320, could be considered fine or even pretty good. While, going at 6 runs an over in an innings of 250 or lower is objectively expensive.

Another curiosity of the tournament was that not all sides played all 3 groups games. Cancellations and tournament progression mean that leaderboards are skewed – i.e. having the most runs or wickets is less valuable if you’ve played more matches. Of course, this is where we can draw on averages, but also, this gives us another reason to pick out some RR and REc analyses to find alternative forms of value in the stats.

So let’s take a close look at the best batters and bowlers throughout the competition and use our stats to rank them. Further on, we will present a team of the tournament based on the stats discussed. Who’s going to make it?

Batting Analysis

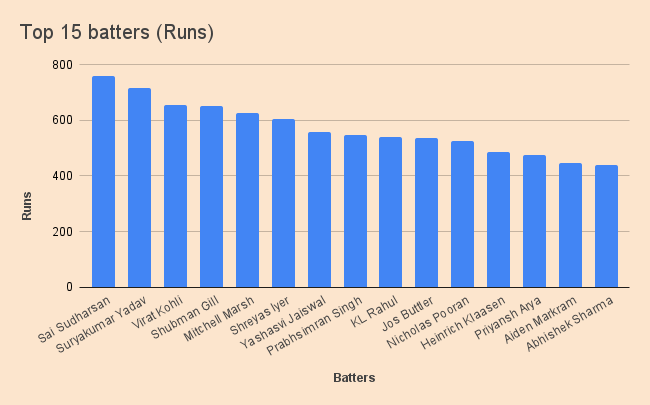

The top 9 batters at the CT, in order of runs scored, were: Rachin Ravindra (263), Shreyas Iyer (243), Ben Duckett (227), Joe Root (225), Virat Kohli (218), Ibrahim Zadran (216), Tom Latham (205) and Kane Williamson (200).

These are the only batters who scored over 200 runs in the competition. Ravindra was named the official player of the tournament, and fairly so, thanks to his two centuries on New Zealand’s way to the final.

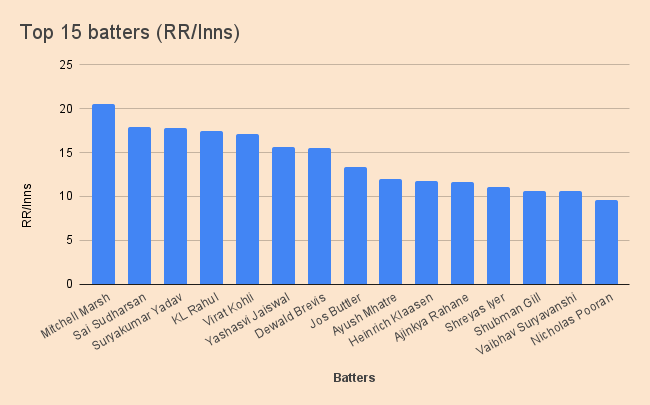

When we look at Relative Runs, however, the leaderboard is a bit different. The top RR scorers across the tournament were: Duckett (151.83), Root (149.84), Ravindra (141.95), Zadran (139.76) and Rassie van der Dussen (93.52).

When we take into account innings batted, the top RR scorers per innings were: Duckett(50.61), Root (49.94), Zadran (46.58), Jaker Ali (36.54), Ravindra (35.49), Towhid Hridoy (33.54), and then Van der Dussen (31.17).

These 7 batters were the only ones to average more than 30 RR per innings. This means, they would typically score more than 30 runs more than the par score of their teammates. That’s a significant contribution. However, only two of those made the official team of the tournament: Ravindra and Zadran, as the chosen openers.

My first argument using RR here is that Duckett and Root are both very unlucky not to be in the team of the tournament despite the fact England lost all three of their matches.

Both of them were in the top 4 run-scorers, had higher averages than Ravindra and Zadran, both scored centuries, and importantly for us, they were the leading RR scorers in total and per innings. For these compelling reasons, I’m calling them the two best batters of the tournament.

There are a couple other points to make here. The Bangladeshi duo of Jaker and Hridoy stick out. I would not have thought of them as standout players but they were according to RR. Partly this is informed by the fact they were in a largely failing side – good players in bad teams will stand out according to RR due to the relative nature of how the stat is formulated.

They put on a massive sixth-wicket partnership of 154 against India when the rest of their side crumbled, one of the forgotten highlights of the tournaments that RR helps us to value.

The same points holds true of Duckett and Root – they outperformed their teammates so much that they have great RR stats. In the case of these two, though, their overall stats also hold up against all the batters in the tournament, impressively.

Bangladesh only played two matches, like Pakistan (due to the sides’ washout), it should also be noted. If we set a parameter for batters who batted a minimum of 3 times (which is reasonable), the top RR per innings players were: Duckett, Root, Ravindra, Van der Dussen (all as above), then: Azmatullah Omarzai (16.58), Ryan Rickelton (15.84), Iyer (15.70), Kohli (10.70), and then sub-10 value batters.

There are a few more honourable mentions to make to players who only batted twice but performed well according to RR per innings, that is, better than Azmatullah but worse than Van der Dussen. Those are: Khushdil Shah (29.55), Josh Inglis (29.39), Alex Carey (28.89), Temba Bavuma (24.26) and Babar Azam (19.54).

There’s a conversation to be had about whether playing more matches in the tournament means you should be considered higher or lower. Playing more can mean you have more chances to improved your stats, but also more chances to lower your average via outs.

Generally, when it comes to something like awards, you want to favour players who went deep in the competition or on to win the thing. I’m going to put that consideration to one side (or rather leave it to the ICC) and present the following based on all of the above:

Batting Awards

Most RR: Ben Duckett (151.84)

Most RR per innings: Ben Duckett (50.61)

Most RR in an innings: Ibrahim Zadran (142.11) vs England

Bowling Analysis

Let’s move over to the bowlers now. The focus of this analysis isn’t going to be wickets – although they play a part in assessing bowlers, obviously – but rather, Relative Economy (REc).

This is our key stat in white-ball cricket because keeping teams to lower totals is more crucially than taking many wickets. To win a Test match, you much take 20 wickets; to win a limited-overs match, you needn’t take 10. In fact, you needn’t take any – although that would be very odd. What we’re saying is, though, REc is our most essential stats for assessing bowlers and we will couple that with wicket taking ability in the conversation that follows.

The top bowlers in the tournament according to wickets taken were: Matt Henry (10), Mitchell Santner (9), Mohammed Shami (9), Varun Chakravarthy (9), Michael Bracewell (8), Azmatullah (7), Ben Dwarshuis (7), Kuldeep Yadav (7) and then a lot who took 6 or fewer.

The bowling averages from those players above were (in order): Varun (15.11 – best in the CT), Henry (16.70), Azmatullah (20), Dwarshuis (21.71), Bracewell (25.12), Shami (25.88), Santner (26.66), Kuldeep (31.85).

The official team of the tournament had a bowling attack of: Henry, Shami, Azmatullah, Varun and Santner, with Ravindra in the top order as an allrounder.

It’s hard to argue too much with that attack – it’s balanced and they all had very good tournaments. But can we find any hidden or extra value using REc? Let’s take a look and see.

According to total REc accumulated (having bowled 10 overs or more in the CT), the best bowlers in the tournament were: Bracewell (-5.89), Abrar Ahmed (-4.64), Mohammad Nabi (-4.6), Adil Rashid (-4.21), Santner (-2.61), Ravindra (-2.54), Axar Patel (-2.43), Taskin Ahmed (-2.15), Keshav Maharaj (-2.08), Nathan Ellis (-2.02). Ravindra Jadeja (-1.97), Noor Ahmad (-1.74), Harshit Rana (-1.49), Wiaan Mulder (-1.28), Varun (-1,25), Naseem Shah (-1.22), and Mehidy Hasan Miraz (-1.15).

All of the above bowlers accumulated more than -1 REc throughout the tournament. Notable bowlers who join this group and bowled less than 10 overs include Matthew Short (-2.48) and Salman Ali Agha (-2.14). This indicates they were underused by their teams.

If we average it out for overs, the best REc per overs bowlers were: Firstly, Short and Salman – again, underused outliers – and then of those who bowled 10 overs or more, in order: Abrar (-0.43), Nabi (-0.31), Rashid (-0.16), Taskin (-0.13), Ravindra (-0.12), Bracewell (-0.12), Harshit (-0.10), Noor (-0.08), Maharaj (-0.07), Ellis (-0.07), Mulder (-0.06), Axar (-0,05), Santner (-0,05), Jadeja (-0.05), Varun (-0.04).

A few things stand out when we look at these top 15 bowlers according to REc per overs bowled. Firstly, most of them are slow blowers, which isn’t hugely surprisingly. Spinners tend to have better economy rates in 50-over cricket as they are used outside the power play and in the slower middle overs heavily. But perhaps more strikingly, the top 4 bowlers are all from sides that were dumped out before the semi-finals.

Just like with good batters in weak teams, economical bowlers in poor teams will standout more with these stats. Rashid is a good example, he’s an outstanding bowling in a losing side that was full of relatively expensive pace bowlers, that is, England. His REc is thus very low. Despite that caveat, his numbers are still impressive.

Another curiosity is how well Harshit Rana performed for India despite later being dropped from the team for the final matches of the tournament in favour of Varun. He was actually the second best pace bowler in the entire competition accruing to REc, albeit having only played two matches.

If we were to pick a bowling attacking from these numbers, including at least two pace bowlers, it would be: Taskin, Harshit, Abrar, Nabi, Rashid with Ravindra chipping in as an allrounder.

Interestingly, Ravindra makes both the top 6 bowlers and batters according to RR and REc – for this reason, his player of the tournament award feels especially justified!

Looking at that above bowling attack, its not bad. And pretty balanced with leg-spin, off-spin and left-arm spin in it. Would it be good enough to beat the team of the tournament? Or more pertinently, would it beat India in Dubai? It’s hard to think so but it would surely be economical! And that’s half the art, right?

It’s notable that India had three spinners in the top 15 REc bowlers. This goes to show just how good they all are but also negatively affects the REc of someone like Shami, who relatively suffered playing with such players, according to these stats.

Shami’s REc per over was 0.08 – meaning he averaged that many runs more per over than his teammates. However, you can’t say he was bad. It’s a quirk of the statistic that it will find value in some players and hide value in others – like all stats.

So, we have our best bowling attack according to REc but what if we limit it to players who played at least 3 times like we did with the batter rankings above? Well, then we would have something like this as an attack: Ellis and Mulder as our best quicks, Nabi, Rashid, Bracewell, with Ravindra again as an allrounder.

It looks a bit closer to a bowling attack capable of beating India and interestingly, has no Indians!

There is one aside to add to this and that is about Nabi, who’s best REc came in the rain-shortened innings against Australia in which he only bowled 3 overs. If we take that outlier innings out of his analysis (which I think is fair considering just how much it skews his score), we could replace him with a player who bowled in three full innings, someone like Maharaj, for example.

Bowling Awards

Best REc accumulated: Michael Bracewell (-5.89)

Best REc per over (min. 10 overs bowled): Abrar Ahmed (-0.23)

Best REc in an innings (min. 5 overs): Abrar Ahmed (-2.94) vs India

Team of the Tournament

Based on the above numbers, here’s our initial team of the tournament (batted at least twice, bowled at least 10 overs):

1. Duckett

2. Zadran

3. Ravindra

4. Root

5. Towhid*

6. Jaker (wk)*

7. Nabi

8. Harshit*

9. Rashid

10. Taskin*

11. Abrar*

*denotes those who only played twice

There are a few things that are bothersome about this team. As discussed, Nabi’s numbers were skewed heavily by one half-innings of bowling of only 3 overs. What’s more, it feels odd to include players who only played two matches. After removing the starred players and Nabi, there are a couple things to then resolve in building our final team of the tournament.

After losing both Harshit and Taskin, the allrounder spot at 7 needs to be a pace bowler and could thus be Azmatullah or Mulder. Mulder makes the top 5 bowlers ahead of Azmatullah but the latter has a superior batting record and a pretty good REc as well. Looking at classic bowling stats, Azmatullah is behind Mulder in terms of average but ahead on wickets and strike rate. It’s genuinely a toss up but I’ll go with Azmatullah at 7 for his all-round success at the tournament and Mulder can be the 12th man.

The keeper’s slot is another question. If we are going to pick a keeper purely based on RR with no matches-played conditions, we would pick Jaker as above. However, he only played twice and in neither match as a keeper, which makes leaving him out even easier.

The next keepers in line based on RR are Inglis and Rickelton. The latter batted 3 times but only played as a keeper when Heinrich Klaasen was out injured, what’s more, he’s an opener. For those reasons, I’ll go with Inglis even though he only batted twice, an exception for positional reasons. In his favour, he did play in 3 matches (all as a keeper) and is the best keeper of the three mentioned.

There is one last question remaining and that is the captain of the side. There is no player in the XI so far that was a team captain at the tournament. For that reason, I am going to select Santner ahead of Maharaj and Noor (one of those would otherwise have made the XI in the bowling group).

Santner’s REc per over was only slightly worse those two and his captaincy in leading NZ to the final was impressive. It’s convenient he’s another slow bowler, so the team retains balance without having to sacrifice much ability or change the allrounder.

So, here we have our final RR team of the tournament:

1. Duckett

2. Zadran

3. Ravindra

4. Root

5. Van der dussen

6. Inglis (wk)

7. Azmatullah

8. Bracewell

9. Santner (c)

10. Rashid

11. Ellis

12. Mulder

It should be noted that while we strayed away from RR and REc slightly to chose a keeper and captain, we haven’t spoken about choosing players based on fielding at all. Someone like Glenn Phillips immediately springs to mind. He hasn’t jumped out of the page in terms of his RR/REc stats but his fielding in the competition and his general all-round abilities got him a place in the official team of the tournament, and that’s fair enough. That’s just not what we’re doing here, but its worth mentioning him as an aside and the issue of fielding in general.

There’s only one question that remains… could this team beat India in Dubai?

Interestingly, we’ve come up with a team that is strikingly similar to India’s in terms of construction – we have a bowling split of 2 pacers (with one being an allrounder) and at least 4 spinners. We have finger and wrist spin, left and right arm options. Crucially, the team bats very deep just the champions with Santner down at 9.

By basing our bowling attack on REc, we have the best options in terms restricting a side’s scoring. As for batting, the players chosen were those who scored in toughest of scenarios.

I wouldn’t go as far as to say this team is better than India’s but I would say they could run them close, much like NZ and Australia both did… and perhaps even closer. It’s a damn good team, that’s for sure and RR and REc have not only helped us pick the side, but find value that was otherwise going unnoticed in the official team of the tournament.